A battle of wills: Frank Ledwidge on why Ukraine should brace itself for a war of attrition instead of hoping for a “game-changer”

It is worth saying that military history offers few, if any, examples of ‘game-changers’. Some campaigns have been heavily affected by certain weapons systems. As an air power historian, the case of the long-range American P51 Mustang fighter aircraft comes to mind. It had a key role in destroying the German Air Force as a fighting force in 1944. However, in that, as in every other case, the P51 was part of a much larger system of systems. The campaign it fought would have been won anyway since the US possessed several other similar aircraft which would have completed the task. We see the same story time and time again.

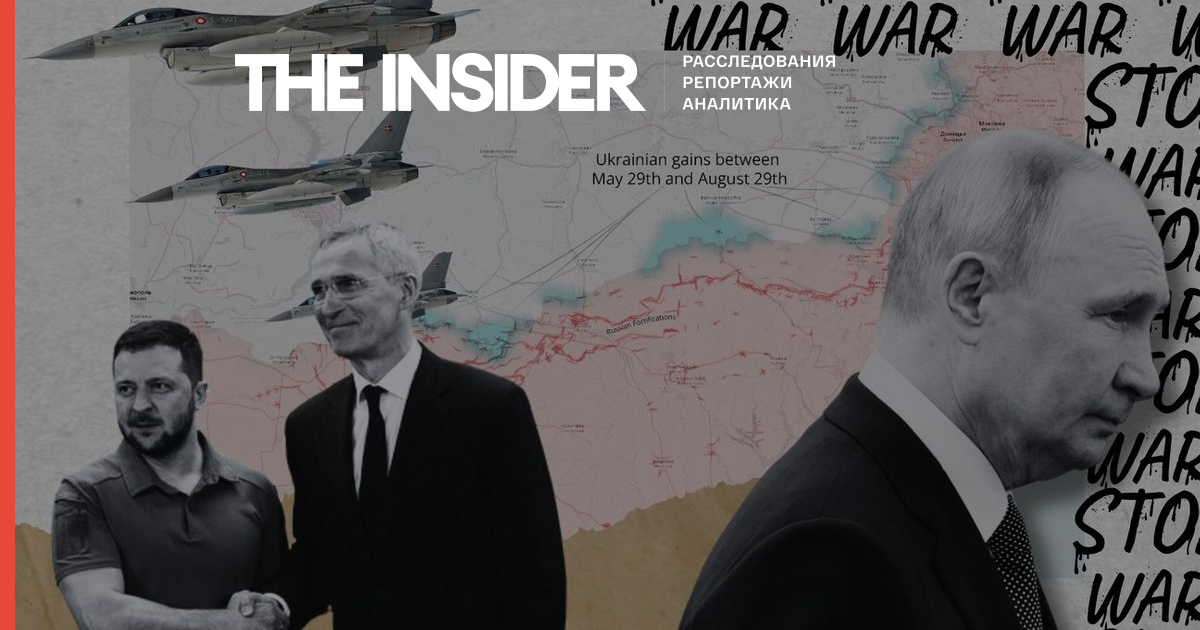

The same general principle applies to ‘breakthrough’ as a significant concept. Most recently, we’ve seen this with Ukrainian claims in Zaporizhzhia. Once again, we are constantly seeking some hope by which the conflict could be brought to a quick, successful end. In other words, could be won. Usually, such hopes prove quickly to be deceptive. Let me offer a couple of examples. On 21st March 1918, in the last year of the First World War, the German Army launched an attack on British lines in Northern France. Catching the British by surprise, they broke the British lines and flowed forward, gaining more land in a day than they had in the previous four years. This was Operation Michael. In a similar surprise attack, in May 1940 at Sedan, the French army was defeated by the Germans in the first major battle of the so-called Blitzkrieg, which eventually drove the French and British allies to the sea. Just over a year later, a vastly larger operation – Barbarossa - broke Soviet lines in June 1941. The Germans pushed forward to the gates of Moscow itself. All of these were ‘breakthroughs’. The reader may see a pattern here. None of them – despite much-misplaced confidence at the time – were decisive. None of them won the war. In the first case, Operation Michael, the British commanders gave a famous order, order ‘Backs to the wall’. The army was quickly reorganized and counterattacked. The Germans, who had not planned for such a large advance, outran their supplies. The British, with their French and American allies alongside them, counterattacked and broke the German Army. The war was over by the end of the year. As for Sedan and Barbarossa, we all know what happened; these were temporary victories. There are hundreds of such examples.

Finally, we have the closely related idea of ‘turning points’. The offensives that retook Kharkiv and Kherson were described in those terms, as was the mutiny of the Wagner Group in July of this year. Everyone knows what happened, it was over in a day, and eventually – as many expected – its leader was killed and Wagner seems to be neutered. Counterfactuals are always interesting, but not very helpful. However, had the mutiny in some way succeeded, as all Ukrainians hoped it would, the outcome might have proved fool's gold in the long term. It is highly unlikely, surely, that any new management of Russia – whoever it was - would simply surrender to Ukraine and call the whole thing off. All that said, of course, no such thing happened. We still seek a genuine ‘turning point’. Unfortunately, such moments are usually recognized only many years after they happened.