A Mysterious Trader of Russian Oil Links Associates of Vladimir Putin and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s friends

An investigation by IStories

Доступно на русскомDate7 Jul 2025AuthorRoman Katin

In this article you will learn

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban is one of Russia’s allies in Europe. He claims that the EU is helping Ukraine at the expense of European interests and that Hungary will not quit Russian oil and gas. Experts and the press suspect that the Russian authorities have given Orban’s inner circle the opportunity to earn hundreds of millions of dollars from energy commodities trading.

At the center of attention is the mysterious trader of Russian oil, Normeston Trading, which in 2009 got half of a gas trader created by Hungary’s largest oil and gas company, MOL, and then transferred its stake to Orban’s friends and their partners.

Normeston Trading itself, on the Hungarian side, is co-owned by people affiliated with Orban’s friends. For years, the press and experts have tried to understand how Normeston could be connected to Russia’s top political circles.

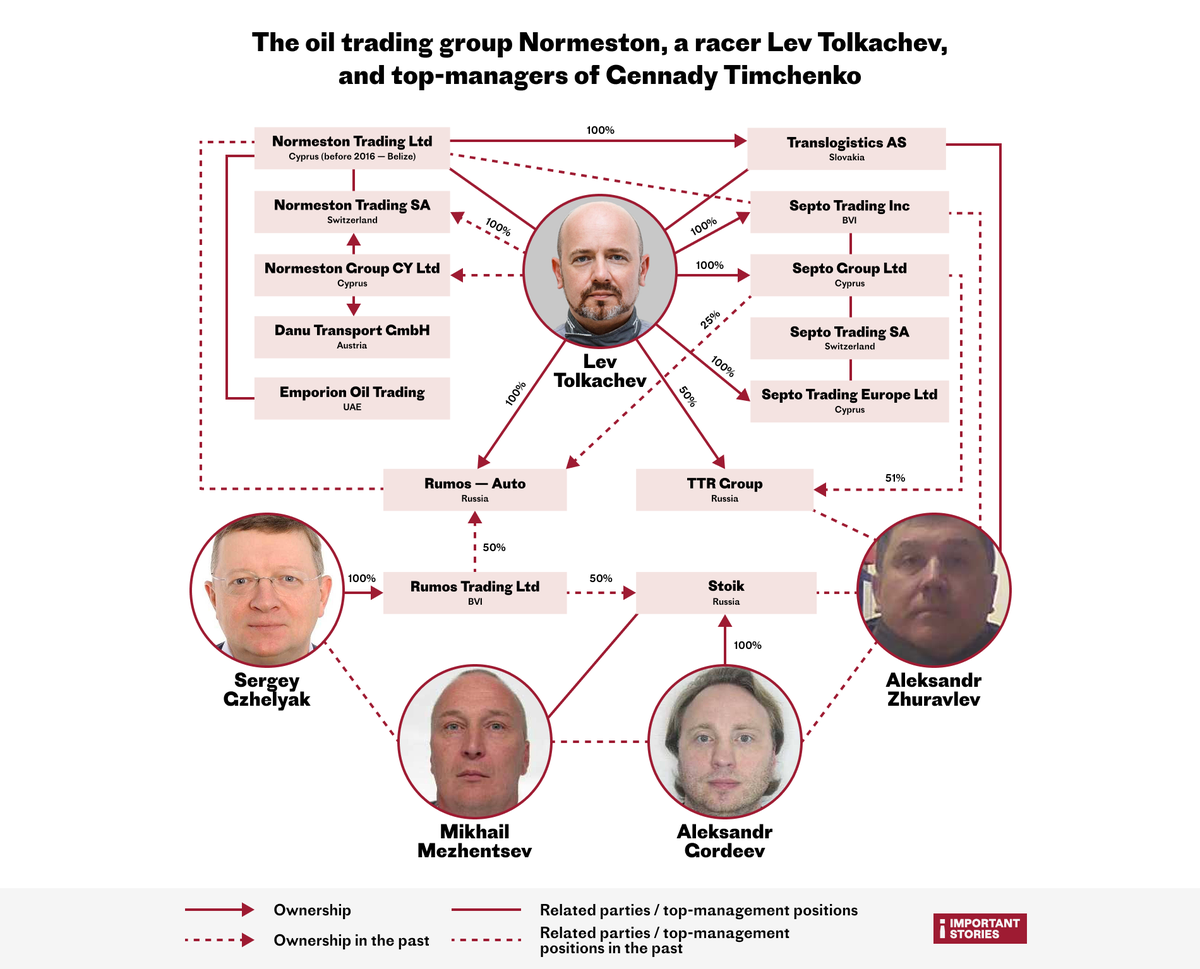

IStories found out that the former Russian owner of Normeston — race car driver Lev Tolkachev — was also a business partner of Gennady Timchenko’s top-managers. Vladimir Putin's close friend Timtchenko was the biggest Russian oil trader before 2014 sanctions. One of his former managers, Aleksandr Zhuravlev, still sits on the boards of some companies in the Normeston group together with the race car driver.

In 2017 and 2018, Cyprus-based Normeston Trading was “under common control” with the Russian company of the race car driver, which was half-owned by another Timchenko top manager — Sergey Gzhelyak. In Cyprus, “common control” means that the companies are owned or their finances are controlled by the same parties.

After the race car driver, the Russian businessman Valery Subbotin became a co-owner of Normeston. Subbotin is a former vice president of Lukoil, who fled Russia in 2016 and settled in Europe, but established business ties with Putin’s friends and the entourage of former pro-Kremlin Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych.

“The mother is a woman”

“The father is a man, the mother is a woman, the fuel price is 480 forints,” — a post appeared on the Facebook page of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban in May 2022. This was a way he reported on his “victory” at the EU summit in Brussels, where sanctions against Russia were discussed. At that time, the embargo on Russian oil supplies to EU countries was introduced with an exception — it did not apply to pipeline deliveries. At the end of 2023, this exception was extended, and Orban says, that he will continue to prevent a complete ban on Russian oil and gas supplies to the EU. On June 23 of this year, it became known that Hungary and Slovakia blocked another EU sanctions package, which would have meant a rejection of Russian energy resources.

Orban, in his speeches, sometimes echoes Russian propaganda. In 2024 he declared, that Europe acts at the behest of the United States and, to its own detriment, supports the war in Ukraine, while Hungary stands apart, guarding its national interests and cannot quit cooperation with Russia, especially when it comes to oil.

Russian oil still flows to Hungary and neighboring Slovakia (and flowed to the Czech Republic until 2025) via the southern section of the Druzhba pipeline, crossing Ukraine.

One of the major suppliers of Russian oil to Eastern Europe — Normeston Trading, is a mysterious trader with an opaque ownership structure.

It is a paradox, but after the sanctions for the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Normeston Trading’s deliveries via Druzhba through Ukrainian territory jumped more than fivefold. And after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 — tenfold. During the lull between these events, deliveries dropped to insignificant volumes.

In 2014, 5.7 million tons of Russian oil were sold to Eastern Europe via Normeston Trading (all further figures are IStories’ calculations based on Import Genius data) — more than a third of the total volume pumped through the southern section of Druzhba at that time. In 2023, about 2 million tons passed through Normeston, including more than 1 million to Hungary, almost a quarter of Druzhba’s deliveries to that country. In total, since 2011, more than 20 million tons of Russian oil worth over $10 billion have been sold to Europe via Normeston Trading.

The intermediary has attracted a lot of attention of Hungarian media and anti-corruption activists. They called Normeston a participant in one of the most “critical episodes in the country’s economic history,” which allowed Orban’s friends to get hundreds of millions of dollars.

IStories found out that the business ties of Russian owners and top managers of Normeston lead to Vladimir Putin’s friends.

How it’s done in Russia. The racer

The roar of engines at the start. The car accelerates to 50 kilometers per hour in less than two seconds, tries to overtake a competitor sharply turning left, and crashes into a green Audi lingering at the starting line. This was the shortest race in Lev Tolkachev’s career in 2020 at the Smolensk Ring track. Tolkachev, a circuit racing driver with number 47, was involved in another incident two years later at the Nizhny Novgorod Ring — entering a turn, he rammed the side of a car overtaking him. Both times, there were no injuries.

It was Tolkachev who was officially named as the owner of Normeston Trading in 2014.

The company was registered in Belize in 2006 and did not disclose its owners. Only in 2014, when Normeston was buying Lukoil’s gas station network in Slovakia, did the local antimonopoly service name the official owners of the oil trader: Lev Tolkachev — from Russia, and Imre Fazakas — from Hungary.

The suppliers of oil and oil products to Europe via Normeston: Russian state companies and members of Putin’s major political partyIn 2014, Normeston Trading became the largest buyer of crude oil from the Russian giant Bashneft — the deal amounted to up to $4.13 billion. And one of the largest buyers of Bashneft’s oil products, for up to $2.4 billion, was a company from the British Virgin Islands, Septo Trading. Septo Trading is officially wholly owned by race car driver Tolkachev, according to available financial reports from Normeston and Septo in the Cyprus registry. Normeston and Septo were “related parties.”

In 2016, after their contracts with Bashneft ended, other companies started supplying them with oil and oil products: Intek-Zapadnaya Sibir, owned by the deputy secretary of the regional branch of United Russia political party and a parliament member of Khanty-Mansi — Ugra Russian region, Sergey Veliky; Slavyansk-Eko, owned by former Krasnodar Region legislative assembly deputy and United Russia faction member Robert Paranyants; Gustorechensky Plot, owned by former Yugra Bank owner, billionaire Alexey Khotin — a figure in one of the largest criminal embezzlement cases in Russia.

In 2023, the main oil suppliers for Normeston Trading were: Tatneft (853,990 tons), controlled by state structures of Tatarstan, the Tatarstan oil company Aloil (704,000 tons), owned by the family of former Tatneft top manager Gali Ganiev, and state-owned Zarubezhneft subsidiaries (272,600 tons).

Tolkachev has worked at Lukoil from the 1990s to the mid-2000s. In 2008, he became general director, and later the owner, of a business in Tver (Rumos-Auto group of companies). There he owns three gas stations, a car dealership selling Russian, Korean, and Chinese cars, a cafe, and a karting center. The turnover of this business in 2024 — about 5 billion rubles ($50 million) — is incomparable to Normeston Trading’s revenue. In 2014 Tolkachev created the Rumos Racing team.

“In Russia under no circumstances could a race car driver, even if he’s a former oil company employee, be the real owner of an oil trading business with contracts worth billions of dollars. It is simply unrealistic if he doesn’t have people with big connections behind him,” a former high-ranking Russian official told IStories. “People involved in Russian oil trading are like exclusive private club members; outsiders simply can’t get in,” says another source — an entrepreneur who was a member of Russian Forbes billionaires list.

The backstory of Normeston Trading confirms it might be true.

Normeston and Putin’s KGB acquaintanceIn 2012, the Polish Dziennik Gazeta Prawna reported, citing its sources, that Normeston was linked to Mikhail Arustamov, former first vice president of the Russian state company Transneft.

IStories’ sources on the Russian oil market confirmed it, adding that Normeston was backed by the interests of Arustamov and his business partner Andrey Bolotov — at the time, the son-in-law of Transneft president Nikolai Tokarev (Bolotov and Tokarev’s daughter divorced around 2018). Tokarev is an old friend of Vladimir Putin. They both served in the KGB and worked in East Germany.

Buying Russian oil via Normeston Trading (and a couple of other traders), European companies could receive additional volumes of oil over official pumping schedules of Transneft, the Polish newspaper noted. And the technical capacities of the Druzhba pipeline were limited for those who did not sign contracts with the same Normeston. While at Transneft, Arustamov was in charge for oil pumping schedules among other things, as former high-ranking Transneft employees and Tokarev’s acquaintances told us. Arustamov himself denied any connection with oil traders.

The racer and Gennady Timchenko’s managers

The business connections of the racer (see diagram), as well as the money flows of Normeston Trading, led to the top managers of Russian billionaire Gennady Timchenko — the longtime friend of Putin. Timchenko owned the famous oil trader Gunvor, which handled up to a third of Russian oil exports. He came under US sanctions in 2014, sold his stake in Gunvor, and since then has not been directly involved in Russian oil trading.

A representative for Timchenko did not respond to IStories’ questions about whether he has any connection to Normeston Trading and why this group has many direct and indirect ties to his top managers. The latter also ignored requests for comment. Gunvor stated that it has never done business with Normeston and is not connected to the company.

Current and former Timchenko managers

Sergey Gzhelyak

Tolkachev’s partner in the Rumos-Auto company, at least until 2019, was Sergey Gzhelyak. Rumos-Auto received loans worth millions of dollars from Normeston and its affiliate, Septo Group.

Since 2007, Gzhelyak has held senior positions in Timchenko’s companies: he was the director of Gunvor in Moscow and headed the offices of the trader’s subsidiaries engaged in logistics and transshipment of oil and oil products in Russian ports. And since 2019 according to his LinkedIn profile, he is managing director of Novatek Gas & Power, the Swiss subsidiary of Novatek, Russia’s second-largest gas producer, owned by Timchenko and his partners. Gzhelyak is Novatek's minority shareholder.

Aleksandr Zhuravlev

From 2012, for 11 years, Aleksandr Zhuravlev worked as one of the directors of the Moscow branch of Tolkachev’s Septo Trading.

In 2017, Septo Trading’s debts to Normeston Trading on loans exceeded $44 million, and in 2020 — $42 million. The loans were unsecured, at a symbolic 0.5–1% annual interest, repayable in 2025.

Zhuravlev worked in Timchenko’s companies from 2009 to 2012: first at the Timchenko-owned Gunvor Novorossiysk Fuel Oil Terminal, which receives oil products delivered by land to the Novorossiysk port and transfers them into the sea tankers. Together with Gzhelyak, Zhuravlev worked at the Moscow branches of Gunvor subsidiaries (Palmpoint International and Sandmark), which handled logistics and transshipment of oil and oil products in Russian ports. At present, Zhuravlev, together with race car driver Tolkachev, sits on the board of directors of the Normeston group’s logistics company — Translogistics (Slovakia), which organizes the transportation of oil products by European railways and rivers.

Aleksandr Gordeev

Gordeev is the CEO and owner of the fuel trading company Stoik. From 2008–2012, it was headed by Aleksandr Zhuravlev, and half of it belonged to a company from the British Virgin Islands, Rumos Trading, which, according to Pandora Papers leaks, was owned by Sergey Gzhelyak.

At the same time, Gordeev worked in the management of Gunvor group companies: since 2007 he was executive director of Palmpoint International, in 2009–2014 (with interruptions) — first deputy general director of Novorossiysk Fuel Oil Terminal, and in 2011 — one of the heads of Moscow office of Sandmark.

In 2010–2012, Gordeev sat on the board of directors of Rosneftbunker together with Timchenko’s son-in-law, Gleb Frank, heads of other billionaire’s companies, and Gunvor employee Viktor Yakunin, son of another Putin's friend from the KGB, former Russian Railways head Vladimir Yakunin. Rosneftbunker (later Ust-Luga Oil) belonged to Gunvor from 2009 to 2015, built a terminal for oil product transshipment in the Ust-Luga seaport and became the operator and owner of this terminal. Stoik, headed by Gordeev, managed to register the website vitinoport.ru. Gunvor negotiated the purchase of the Vitino oil port in Murmansk Oblast, but the deal did not go through.

Mikhail Mezhenzev

The first deputy general director of Stoik, Mikhail Mezhenzev, came from the same companies as Gordeev, Zhuravlev, and Gzhelyak: he was an advisor and director at Palmpoint International and Sandmark branches from 2007 and 2011. In 2014, he headed Gunvor’s Moscow office. Before 2008, Mezhenzev worked at Sovcomflot — Russia’s largest state shipping company specializing in oil and gas transportation. Sovcomflot provided Gunvor with tankers for oil shipments.

Until 2013, Mezhenzev chaired the board of directors of Rosneftbunker, where Timchenko’s son-in-law sat. From 2009 to 2010, he was president of Transnefteprodukt, part of Transneft. After the war began, Mezhenzev was noticed in the management of oil traders among the largest dealers of Russian oil — Concept Oil Services and Demex Trading. It was reported that Concept Oil could buy Russian oil above the price cap set by the EU. And Demex came under US sanctions for trading Russian oil.

Former Lukoil vice president and Putin’s friends

A new, bright villa with a pool and a park on the French Riviera is surrounded by a fence, topped with three rows of barbed wire, and lined with surveillance cameras along the perimeter. A person involved in the villa’s maintenance was impressed by the security measures and the large number of guards; he assumed the villa belonged to Rosneft chief Igor Sechin. But according to documents at IStories’ disposal, it belonged to the family of another Russian oilman — former Lukoil vice president and ex-chairman of the board of Lukoil’s oil trader Litasco, Valery Subbotin.

In 2016, while the villa was still under construction, Subbotin left Russia. “In fact, he was being rescued,” Russian Forbes reported. The state-controlled Rosneft at that time took control of Bashneft. Contracts with Lukoil were immediately terminated — they “raised questions,” Forbes quoted Rosneft press secretary Mikhail Leontyev. In 2017, Lukoil announced Subbotin’s resignation from the central office, and until January 2020, he headed the board of directors of Litasco.

Having fallen out of Sechin’s favor, Subbotin settled in Europe. He is now a citizen of Cyprus, living in Monaco, — as he is listed in European commercial registries. But Subbotin did not leave the Russian oil trading business.

In the summer of 2023, Normeston Trading won a tender to supply oil to the Czech Republic worth more than a billion crowns (over $45 million at the then exchange rate). Czech media reported that the company was backed by Valery Subbotin. Since April 2023, his Valna Holding Cyprus has owned 49.9% of Normeston, according to both companies reports.

IStories found out that Subbotin could have become a co-owner of Normeston Trading in 2016, after the first wave of anti-Russian sanctions.

Peculiarities of OwnershipBetween 2016 and 2021, Normeston’s ownership was convoluted. After 2016, race car driver Tolkachev ceased to be an owner of Normeston, remaining a board member of the group’s subsidiaries and owner of affiliated companies (Septo). In the 2017 and 2018 financial reports, Normeston Trading (Cyprus) was still described as a company “under common control” with Tolkachev’s Russian Rumos-Auto. In Cyprus, this means that both companies were owned or their finances were controlled by the same parties. Notably, at that time Rumos-Auto was half-owned by Timchenko’s top manager, Sergey Gzhelyak. But his name never appeared in Normeston’s reports.

Subbotin’s British company became the owner of 49% of Normeston Trading only in 2021 (now this stake in Normeston is owned by Subbotin’s Valna Holding Cyprus). However, in 2016, when Normeston Trading moved from Belize to Cyprus, its shares were distributed among two Hong Kong companies and an offshore firm from the British Virgin Islands, Hildale Holdings (which held the largest stake in Normeston — 49,9%).

According to the Pandora Papers leak, obtained by The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the beneficiary of Hildale was 63-year-old Greek citizen Georgios Dematas, living in London. He was listed as the owner of more than 46 companies, so he does not appear to be the real owner. As IStories found out, from 2014 to 2016, Dematas and Subbotin flew together six times on a Dassault Falcon (ES-TEP) business jet to Miami, Nice, and Geneva. Dematas was also listed as the previous owner of several Subbotin's companies.

The presence of former Lukoil top manager Subbotin in Normeston seems logical. Previously, more than 40% of oil deliveries via Druzhba were provided by Lukoil. When Ukraine imposed sanctions against Lukoil in 2024, its oil deliveries via Druzhba through Ukrainian territory were stopped for some time, causing great concern at the highest levels in Hungary and Slovakia. Lukoil has been replaced by the Hungarian oil and gas company MOL (it buys the same Russian oil at the Belarusian-Ukrainian border, and via Druzhba through Ukraine territory it is transported as the oil of MOL).

Without you, there is no us Support IStories — it helps us to continue telling the truthDonateNormeston Trading has never faced any restrictions. According to ImportGenius, it did not buy oil directly from sanctioned Lukoil. And Valery Subbotin left Russia long ago and became a European. But, as IStories noted, Subbotin, who escaped from Sechin, managed to establish business ties with other friends and acquaintances of Putin, people associated with their business interests, as well as with the entourage of former pro-Kremlin Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, who fled to Russia after mass protests in Kyiv in 2014.

From Medvedchuk to Traber

Nisan Moiseev (left), Viktor Medvedchuk

IStories found out that since at least 2020, Normeston Trading became a partner of Swiss based oil trading company Proton Energy Group (now Epsilon Holding). In particular, Normeston guaranteed the payments of $18 million to Proton via Hungarian OTP-Bank, according to Normeston’s financial report.

The owner of Proton Energy is Israeli businessman Nisan Moiseev, a former owner of a Ukrainian gas station network, previously owned by Russian state controlled Rosneft. He was also the largest supplier of Rosneft oil products to Ukraine. Moiseev himself called himself a friend of pro-Russian Ukrainian politician, Putin’s kum, Viktor Medvedchuk, while Ukrainian media hinted that Moiseev was Medvedchuk’s “trusted person” in business. Moiseev denied this.

Photo: Reuters

Sergey Kurchenko

IStories also found out that Subbotin’s European business included the companies of the oil trading group Eminent Energy with a 45% stake in an oil products terminal in Antwerp. Reports from Eminent group of companies show that at least since 2023 and until February 2025, Subbotin was the “main controlling person” of Eminent Energy UK Ltd. Since 2012 and at present, the company has been wholly owned by Cyprus-based Eminent Energy.

Subbotin's Valna Holding Cyprus is 100% owner of Eminent Logistics with a stake in the Antwerp terminal.

Eminent Energy was also linked to Ukrainian assets of Sergey Kurchenko — a Ukrainian businessman from Yanukovych’s entourage who fled to Russia. Since 2014, Kurchenko has been under restrictive measures by the European Union in connection with a Ukrainian criminal investigation, since 2015 — under US sanctions, and since 2022 — under EU sanctions.

Eminent Energy was mentioned in documents of Ukrainian courts as a participant in a scheme for smuggling fuel by Kurchenko’s VETEK group through terminals in Kherson (they were arrested). According to reports from Cyprus-based Eminent Energy, it lost control over certain assets in Kherson worth $10 million, as “they became the subject of a major investigation” in Ukraine and “were seized.”

Photo: Reuters

Mikhail Skigin, heir to Dmitry Skigin

One of the major partners of Subbotin-linked Eminent Energy is the oil trader Horizon International Trading AG, IStories found out. In 2021–2022, Eminent supplied Horizon International Trading with more than 189,000 tons of oil products.

Horizon was founded by Dmitry Skigin (died in 2003) — a St. Petersburg businessman whose companies got a key position in the city’s fuel and energy complex since the 1990s. Skigin’s partners included St. Petersburg crime bosses (in particular Ilya Traber, nicknamed the Antiquarian, a figure in the Spanish “Russian mafia” case). After Skigin’s death, his assets passed to his sons Mikhail and Evgeny.

In 2015, Skigin’s former partner Maxim Freidzon claimed that Dmitry Skigin, allocated a small stake in his oil trading business as a bribe for Putin. “They agreed on 4%,” Freidzon said. The Russian president’s press secretary strongly denied this.

Photo: PNT

Ilya Traber (left), Anatoly Yablonsky

In 2021–2022, one of Subbotin’s Eminent Energy largest partners was the Moscow company Rusinvest, owned by little-known Russian entrepreneur Anatoly Yablonsky, IStories found. Rusinvest supplied Eminent Energy with more than 1 million tons of oil products worth $521 million, according to ImportGenius. Kommersant called Yablonsky an old acquaintance of Subbotin.

According to IStories’ sources, Yablonsky is closely connected with senior FSB officials. He suddenly appeared on the Russian market and was associated with Ilya Traber (reportedly — Russian mobster), who controlled the St. Petersburg seaport and oil terminal. Through Rusinvest, Yablonsky was Traber’s partner in 2019–2021 in the company operating the Ust-Luga seaport (New Municipal Technologies). Traber is a longtime acquaintance of Vladimir Putin. The Russian president’s press secretary confirmed Putin knew Traber.

Photo: S.M. Kirov Military Medical Academy; Government of Voronezh Oblast

Ilgam Ragimov

In 2019, Subbotin participated in the purchase of a stake in the Antipinsky oil refinery, as reported, together with Putin’s friend Ilgam Ragimov (the refinery later went to Yablonsky).

Ragimov is a classmate of Putin from the law faculty of Leningrad State University, who also practiced judo in his youth. According to Russian Forbes, Ragimov in his interviews confirmed that he and Putin have been “friends for 40 years.”

Photo: Institute of Legislation and Comparative Law under the Government of the Russian Federation

Nikolai Yegorov

In 2019, Subbotin bought a stake in the Antipinsky oil refinery from Putin’s friend Nikolai Yegorov, as Kommersant business daily reported. Yegorov is another of Putin’s classmates and a founder of the law firm Yegorov, Puginsky, Afanasiev & Partners. Russian Forbes reported that Yegorov launched Putin’s political career by introducing him to St. Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak in the early 1990s.

How it’s done in Hungary. Orban’s friends

Summer 2007. Viktor Orban, once Hungary’s youngest prime minister, walks along the outskirts of the Romanian resort town Baile Tusnad in Transylvania and turns toward the stone-paved terrace of a restaurant at a local hotel.

“Oh, here are the representatives of international capital!” he greets a man at a corner table, who immediately leaves his company and shakes Orban’s hand. They laugh, joking that Orban couldn’t get a room at the hotel because his friend had bought up all of them, and Orban pats him on the shoulder.

The “representative of international capital” has often been seen together with Orban at football matches — this is his friend, former banker Zsolt Hernadi, who has headed Hungary’s largest oil and gas company, MOL since Orban’s first term as prime minister.

MOL has long been a partner of Normeston Trading. In 2021, the Normeston group sold MOL a network of 16 former Lukoil gas stations in Slovakia. And in 2022 — a network of 79 gas stations in Hungary. But the main deal took place back in 2009, when MOL sold Normeston half of the gas trader MOL Energy Trade (later renamed MET). Just two years later, Normeston's stake in MET was ransferred to Orban’s friend, Hungarian entrepreneur Istvan Garancsi, and his partner Gyorgy Nagy (MOL, Garancsi, and Nagy ceased to be MET owners in 2018). MET is now a major gas trader with a turnover of almost 18 billion euros, operating in 17 European countries.

It was the deal with the gas trader MET that Hungarian anti-corruption researchers called one of the most “critical episodes in the country’s economic history.”

Thanks to decisions by the Hungarian authorities and with the tacit consent of the Kremlin, MET received unique opportunities: despite Hungary’s long-term contract with Gazprom, MET purchased natural gas at a low price on the spot market and sold it in Hungary. This allowed Orban’s friends and their partners — MET’s co-owners — to earn at least $200 million in just one year (according to reports, MET’s net profit from 2012 to 2017 exceeded $421 million), to the detriment of both Gazprom and the Hungarian budget, researchers noted, pointing out that the Russian authorities and Gazprom could have forced Hungary to honor the gas contract, but for some reason they did not. The reason, according to researchers and a Direkt36 source in the Hungarian government, could be simple: by allowing Orban’s friends to earn millions, the Russians were building informal ties with the Hungarian elite.

The situation with Normeston Trading may be the same. A former member of the Russian Forbes list noted that Russian oil export is heavily controlled by Russian authorities. They could easily cut off supplies through Normeston, and if that doesn’t happen, then allowing Orban’s people to earn money from trading Russian enegry commodities fits the Russian policy of forging connections.

Trusted people

Imre Fazakas who owns 16,7% of Normeston, is an old acquaintance of MOL chief Hernadi; he was a consultant for MOL in 2009 and sat on the boards of its subsidiaries (including MET together with Russian race car driver Tolkachev). Fazakas has been familiar with the Russian oil and gas sector since Soviet times.

“I had to fly to Moscow several times a year,” Fazakas said when asked in an interview with the Hungarian magazine Faklya in 1986 where he learned Russian so well. Since the late 1970s, he studied and worked in the USSR, and in the 1990s spent a lot of time in Russia serving oilmen.

Fazakas, 68, received a technical education in Lviv in 1979 — majoring in “Informatics”, and in Hungary started working for the famous electronics manufacturer Videoton and was assigned to the foreign trade department. In the 1980s, he was deputy director of the Videoton center in Moscow — Hungarian electronic equipment was installed, for example, on oil drilling rigs, — a computer collected and processed information about extracted oil. Soviet geologists and transport enterprises were also Videoton’s clients.

“Videoton was not just TVs producer — the company was important for the military industry and had serious ties to state security,” a former Hungarian official with many years of experience in Russian-Hungarian business told Direkt36, our partner for this investigation.

For the Hungarian oil and gas company MOL and its head Hernadi, Fazakas, according to a source, became a person who may ensure informal ties with Russia in oil deals.

Another Hungarian co-owner of Normeston (33.4%) — The Madera Investment Fund — is linked to one of Hungary’s most influential businessmen, Gyorgy Nagy, a business partner of Orban’s old friends, Istvan Garancsi (they received part of Normeston’s stake in MET) and a banker Sandor Csanyi — one of the richest Hungarians.

Nagy is also no stranger to Russia — he graduated from MGIMO (Russian elite institute). And during Orban’s premiership, Nagy’s company Jet-Sol received, without a tender, a contract from the Hungarian state post office for IT services worth 1.8 billion forints (about $5 million). The same company provided service to Hungary’s largest OTP Bank, headed by close Orban ally Sandor Csanyi who's wealth in 2025 was estimated at €1.47 billion.

Nagy is a partner of Csanyi in a major meat processing business. And MOL headed by Orban’s friend, Zsolt Hernadi became a client of Nagy telecom company Café Group. In 2024, Nagy ranked 35th among the richest Hungarians.

In Moscow, Normeston Trading’s representative office is located in a business center on Klara Tsetkin Street, occupied by companies linked to OTP Bank, the son of its head Sandor Csanyi, Attila, and Gyorgy Nagy.

Orban’s friends

Istvan Garancsi

Garancsi is often seen in the VIP box at football matches with Prime Minister Viktor Orban and MOL chief Zsolt Hernadi. Since 2007, Garancsi has been the owner of the Fehervar football club (formerly Videoton), of which Orban is a fan, and is known for saving the club from bankruptcy. Since 2010, the club has been sponsored by MOL.

In the 1990s, Garancsi worked at Hungarian OTP Bank, and his first serious business was started with Hernadi. In 2001, together with the bank, they managed to buy at a very favorable price a state company (CD-Hungary) which was managing diplomatic real estate in Budapest, the authorities decided to privatize it during Orban’s first term as prime minister in 2001. In 2011, Garancsi became the prime minister’s representative in charge for the development of tourism, road network, and transport.

In 2018, it became known that Orban’s son-in-law, Istvan Tiborcz moved his real estate company to a new office, a mansion in a prestigious district of Budapest. The mansion was owned by Garancsi, Hernadi, and OTP Bank head Sandor Csanyi company, as Direkt36 reported.

In 2014, Garancsi became co-owner of the construction company Market Építő Zrt, which the following year won a tender for the design and construction of facilities for the world aquatics championship in Swiss Lausanne (worth 38.6 billion forints — almost $530 million); Orban agreed with the International Swimming Federation about the championship in 2017.

In 2024, Garancsi ranked 9th among the 100 richest people in Hungary, with a fortune of 172 billion forints ($470 million).

Photo: Laszlo Szirtesi / Alamy

Zsolt Hernadi

Hernadi has worked at various European banks since the late 1980s, and in 1999, during Orban’s first term as prime minister, joined the board of directors of MOL and in 2001 became group CEO.

Under him, MOL transformed from a national company into an international corporation. After MOL gained control and management powers in Croatia’s largest oil and gas company INA in 2009, a criminal investigation was started in Croatia — the country’s former prime minister Ivo Sanader was accused of taking a bribe for transferring management rights over INA to MOL.

According to the Croatian investigation, the bribe of €10 million was given through Fazakas company Hangarn Oil (and one more company linked to him) as payment for consulting services to a friend of the Croatian prime minister. Hernadi in Croatia was sentenced in absentia to two years for bribing Sanader (the former prime minister received six years).

Subsequently, the UN Commission on International Trade Law and then an American arbitration panel, in response to MOL’s lawsuit in 2022, ruled that the bribery allegations were unfounded. Croatian authorities believe the sentences were fair. Fazakas was a witness in the case and denied giving a bribe.

Photo: Attila Kisbenedek / AFP / Scanpix / LETA

Viktor Orban, the owners of Normeston Trading, and other individuals mentioned in this investigation did not respond to IStories’ requests for comments.

In a recent June interview, Orban declared, that if Putin comes to Hungary, he will be received “with all due honors.”

Daniel Szoke (Direkt36) and Dmitry Velikovsky contributed to this article